Overview

Contact

What Is Shoulder Stabilization Surgery?

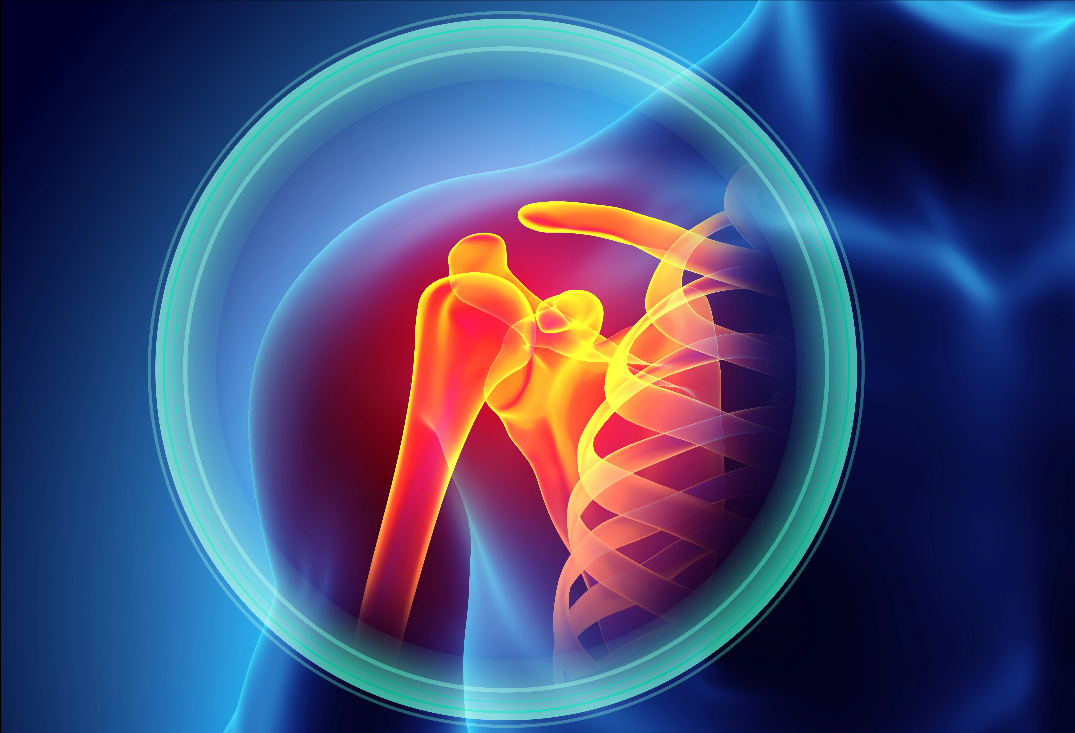

The shoulder, or glenohumeral joint, is a ball-and-socket structure where the humeral head (ball) articulates with the shallow glenoid cavity (socket) of the scapula, allowing extensive range of motion for overhead and rotational activities. Stability relies on a combination of static stabilizers—like the glenoid labrum (a fibrocartilaginous rim deepening the socket by 50%), joint capsule, and ligaments (e.g., glenohumeral ligaments)—and dynamic stabilizers, including the rotator cuff muscles and scapular positioning. The labrum acts as a bumper, enhancing congruency and sealing the joint for negative intra-articular pressure, while the inferior glenohumeral ligament (IGHL) provides anterior restraint during abduction and external rotation.

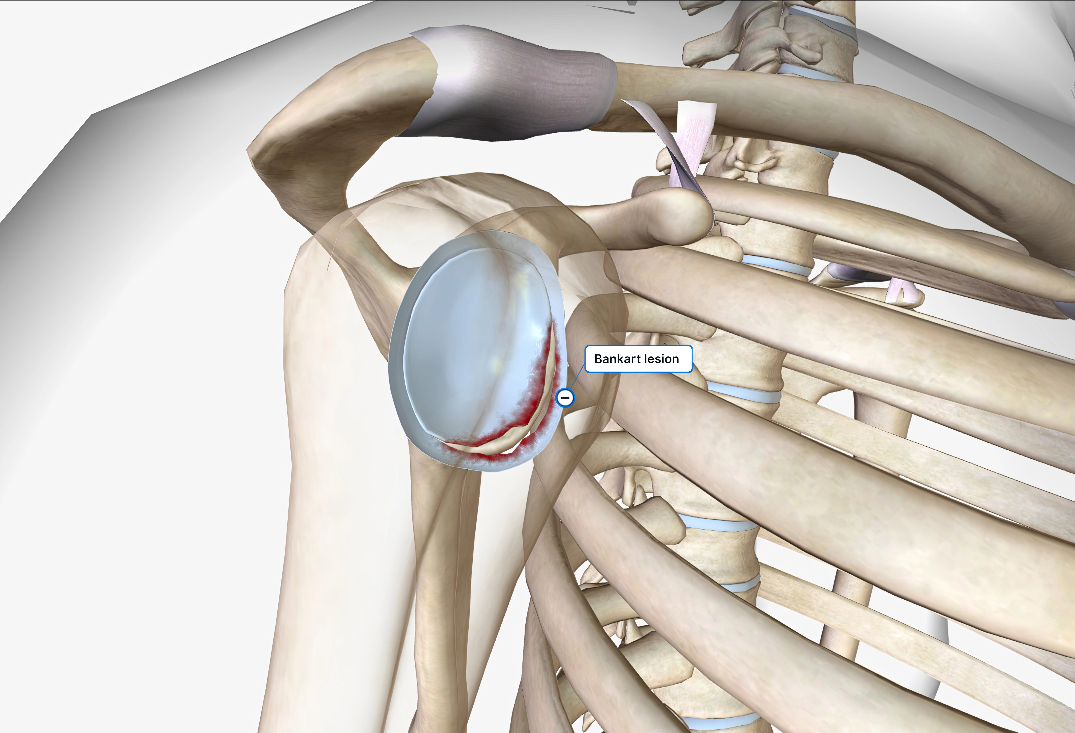

Pathoanatomy of shoulder instability often stems from traumatic dislocations (e.g., from falls, collisions in sports like football or skiing) or atraumatic causes (e.g., hyperlaxity in swimmers or gymnasts), leading to recurrent subluxations or dislocations. Anterior instability, the most common (95% of cases), typically involves a Bankart lesion—a tear of the anteroinferior labrum detached from the glenoid rim, often with capsular stretching or an avulsion of the IGHL. This reduces containment of the humerus on the glenoid and causes apprehension/fear during overhead motions. Posterior instability (5-10%) features a reverse Bankart lesion, where the posteroinferior labrum tears, commonly from seizures, electric shocks, or repetitive microtrauma in weightlifters, leading to pain and weakness in internal rotation or adduction. In cases of significant bone loss, anterior glenoid defects (>20-25% surface area) or engaging Hill-Sachs lesions (posterolateral humeral head defects from impaction against the glenoid) exacerbate instability, increasing recurrence risks post-soft tissue repair alone. Symptoms include recurrent dislocations, apprehension, pain, decreased strength, and positive tests like the anterior apprehension or load-and-shift maneuvers. Untreated, chronic instability can lead to glenohumeral osteoarthritis, nerve damage, or rotator cuff tears from repeated trauma.

At OV Surgical, we advance shoulder stabilization surgery in Canada with arthroscopic and open techniques tailored to the instability pattern and bone involvement, minimizing downtime and optimizing results. Through small incisions (less than 1 cm), our surgeons use an arthroscope to visualize the joint, debride damaged tissue, and address associated injuries like SLAP tears or capsular laxity. For anterior labral repair (Bankart procedure), the detached labrum is mobilized and reattached to the glenoid rim using bioabsorbable suture anchors, with capsulorrhaphy to tighten the stretched capsule via plication sutures, restoring the bumper effect and tension. Posterior labral repair mirrors this, reattaching the reverse Bankart lesion with anchors placed along the posterior glenoid, often combined with capsular shifts for enhanced posterior restraint. In cases of bone loss, we incorporate remplissage—infilling the Hill-Sachs defect by suturing the infraspinatus tendon and posterior capsule into the lesion, converting it to an extra-articular structure to prevent engagement—or the Latarjet procedure, an open coracoid transfer where the coracoid process (with attached conjoined tendon) is grafted to the anterior glenoid, providing a bony buttress, sling effect from the tendon, and increased glenoid surface area. Combined remplissage and Latarjet may be used for severe bipolar bone loss.

Recovery

Our evidence-based protocols use cryotherapy, neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES), and progressive physiotherapy, tailored to procedure type (soft tissue vs. bony) and direction of instability. In the protection phase (0-6 weeks), patients wear a sling (neutral rotation for anterior, external rotation pillow for posterior) to immobilize the joint, allowing gentle passive range of motion (PROM) under guidance—forward flexion to 90 degrees, external rotation to 30-45 degrees for anterior repairs—to prevent stiffness while protecting the labral anchors. Pain is managed with multimodal analgesia to reduce swelling and promote early mobility.

From weeks 6-12 (active-assisted phase), the sling is discontinued, and active-assisted range of motion (AAROM) progresses with pulleys or therapist assistance, aiming for full passive ROM while avoiding provocative positions (e.g., abduction-external rotation for anterior instability). Isometric exercises for rotator cuff and scapular stabilizers begin to restore neuromuscular control and prevent compensatory patterns. By weeks 12-16 (active strengthening phase), full active ROM is targeted with resistance training using bands or weights for internal/external rotation, scapular protraction/retraction, and elevation, emphasizing eccentric loading for dynamic stability. Advanced phases (16+ weeks) include proprioceptive drills, plyometrics, and sport-specific simulations (e.g., throwing programs for overhead athletes). Full motion is typically achieved by 8-12 weeks, strength milestones by 3-6 months, and clearance for contact sports or heavy labor by 4-9 months, verified through tests like isokinetic strength assessments (>85-90% symmetry), apprehension-relocation tests, and functional scoring (e.g., Rowe score). Psychological readiness addresses apprehension through confidence-building exposures.

Benefits

With success rates of 85-95% for labral repairs (recurrence <10%) and 90-95% for bony procedures like Latarjet (recurrence <5%), private shoulder stabilization at OV Surgical restores joint stability, prevents re-dislocation, and supports return to sports and daily life. Patients report enhanced function, confidence, and quality of life, backed by meticulous follow-up and data-driven protocols.

FAQ

Contact